IN April 1889, four French showmen were badly beaten and their two dancing bears killed following false rumours that the animals had killed a child. The incident made a few paragraphs in the local newspapers and was picked up by other papers.

It seems unlikely material on which to base a legend that has lasted 130 years and is still widely known through the Forest and beyond.

But then the cast of characters drawn into it over the years, from a former American slave to a now-forgotten French general and a string of writers, also appears unlikley.

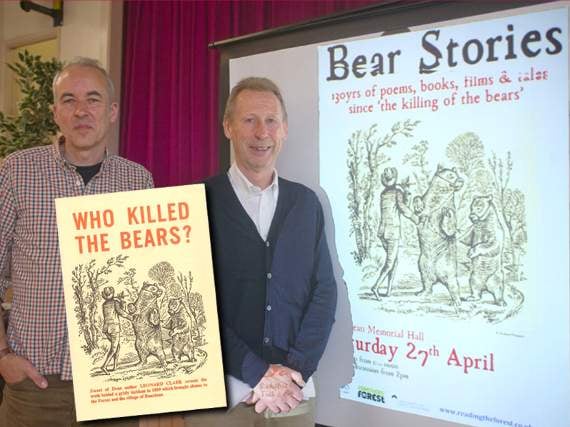

The story of the bears – and its staying power – was the subject of an exhibition and a talk on Saturday (April 27), the day after the 130th anniversary of the events which are still closely associated with Ruardean and Cinderford.

The day was organised by Reading the Forest, a community project led by University of Gloucestershire academics working with volunteers to showcase the literary heritage of the Forest.

The story of the bears shows how a small story can become a big story when people start to manipulate it, said Roger Deeks of Reading the Forest.

The first use – or more accurately abuse – of the story from outside the Forest came from a piece in the Cheltenham Chronicle which portrayed the “harrying of luckless foreigners by these savages of the Forest of Dean” as a “disgrace to Gloucestershire and to England.”

But this wasn’t just a case of snobbishness towards the ‘savages’ on the far side of the Severn, there was a clear political motive with the incident being used by the Tory newspaper to beat the Liberals, particularly the sitting MP, Godfrey Samuelson, and the man who would succeed him, the radical Charles Dilke.

Both were advised to control the ‘lawless passions’ of their constituents, particularly if – and this was another great bone of contention with the Tory Chronicle – Forest miners were to cast their vote for the first at the forthcoming General Election.

The paper also played up the potential damage of relations with France. It was reported that there had been protests from the French consul and the journalists also fretted about how it would go down with General Boulanger.

Although now almost completely forgotten on this side of the Channel, in 1890 the exiled General Boulanger was ‘a big deal’, said Mr Deeks.

Boulanger was the leader of the faction that wanted to avenge the national humiliation of defeat by Germany in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, and that made him attractive to British politicians who were eyeing a growing Germany with suspicion.

Mr Deeks said: “What we have at the start is a little story that becomes a big story when people start manipulating it. We have people who chase bears down the road being given the vote, and two weeks later it’s international, it really is that serious.”

“But while Foresters would get used to calls of “bear killers” if they ventured into other parts of Gloucestershire, at home for many years it was a question of pointing the finger, with Ruardean blaming Cinderford for the incident and vice-versa.

“From outside the Forest, it is evidence of simplicity and ignorance – sometimes people will run with it because they want to think of the Forest in that way, to demonise Foresters.

“Within the Forest it was who was to blame, it was Cinderford v Ruardean, an insider joke.”

But like the people of Hartlepool who have had to put up with jibes of ‘monkey hangers’ since an incident during the Napoleonic Wars, Foresters have come to take ownership of the insult.

So who first lit the touch-paper with the cry of ‘Who killed the bears?’ That dubious honour goes to one ‘Six Fingered Jack’, a 70-year-old former American slave who begged his way around the south-west of England.

His motive was simple – he wanted a few days in the cells – and by shouting out that phrase in a Cinderford pub, he caused a fracas which made his wish.

And there it may have stayed, a way of goading people, but what drove it forward was the stories being picked up by writers, some taking a humorous look and others taking darker lessons.

The first to use the story was FW Harvey in his humorous poem Warning and later Harry Beddington, who wrote a long poem in his book Forest Humour.

The first to see racist overtones in the story was John Moore in his 1954 book White Sparrow, and Dennis Potter’s 1968 television play, A Beast With Two Backs, which was based on the incident sparked outrage over depicting a dislike of foreigners. A letter in the BBC archives states that the filming of Potter’s play states that the presence of cameras had “genuinely stirred up considerable agitation in various quarters.”

Forest poet Leonard Clark also examined the incident in his 1964 book Who Killed The Bears? And although arguments over the bears are unlikely to stir up such passions today, the legend lives on and is still seized on.

BBC Radio Gloucestershire’s Kate Clark, who chaired a discussion, said that when she and her husband moved to Ruardean 11 years ago, friends advised them “not to mention the bears”.

She added: “The legacy is still rife.”

----

A case of rough justice?

SEEN through the eyes of a modern policeman, one of the most interesting aspects of the incident was the need for a spot of quick justice rather than ensuring those actually responsible were collared.

Chief Inspector Richard Pegler of Gloucestershire Police took part in the event to ‘keep the peace’ at the opening between Mayor of Ruardean Neil Jones and former Cinderford mayor Max Coborn.

Ch Insp Pegler said: “What’s interesting was that there was a need to apply some swift justice and for justice to be seen to be done.

“What intrigues me is that there was a very quick round up of suspects, and I wonder if there was a bit of not wanting to favour either side, so there are a similar number of people held responsible on both Cinderford and Ruardean sides.

You look at the cruelty (of dancing bears) and that there was a collection to pay the Frenchmen back so there’s a really interesing dynamic to it.

“If you weave into that a modern view of what had happened – the community tensions, the fact there could have been a hate crime, and were the Frenchmen targeted because they were French, not because they had a bear?

“We have a far better understanding of our communities as a police service in this day and age.

“We have community police who would quickly understand who was responsible,” he added.

“Our processes are such that we would look for a greater weight of evidence, so we would be able to narrow down those who were directly responsible so there would be a far greater sense of justice,” he said.

“We’d be smarter about the investigation, more professional – we’ve got a great constabularly in Gloucestershire where we are very well equipped to deal with major crime.”

.jpeg?width=209&height=140&crop=209:145,smart&quality=75)

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.